Since the 1922 revolts in British-mandate Iraq, Kurdish leaders have been advocating for autonomy for the part of Kurdistan that was incorporated into Iraq. The pursuit of autonomy for Iraqi Kurds has been a struggle spanning a century. Following the initial Iraqi-Kurdish autonomy agreement in 1970, the Iraqi government launched a campaign of ethnic cleansing to maintain control over certain regions. The wars launched by the Iraqi government on Kurdish population persisted from the 1970s through the Iran-Iraq war in the 1990s, reaching its peak with Saddam Hussein’s Anfal Genocide in 1988, which included a chemical gas attack. While the establishment of a no-fly zone by the United States in 1991 provided some degree of autonomy, it was not until the adoption of the 2005 constitution that Iraqi Kurds finally achieved constitutional autonomy through the creation of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). However, the federalist system in Iraq has encountered various challenges, including issues related to power sharing, resource allocation, and social cohesion among its diverse ethno-sectarian groups. These challenges continue to impede the full realization of Iraqi federalism and pose ongoing obstacles to the stability and unity of the country.

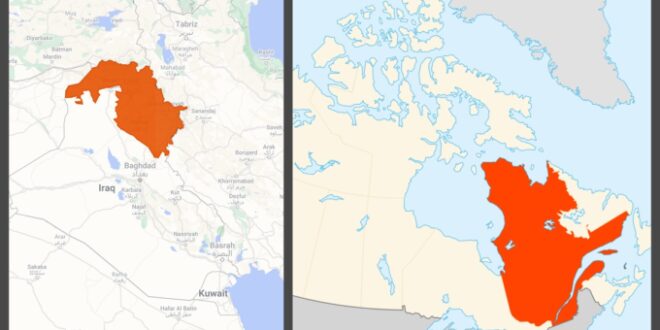

In considering the challenges posed to Iraqi federalism, there are numerous historical experiences that can be referred to, one such being Canada. The most prominent scholar to draw this parallel was John McGarry, who compares Quebec’s self-governance movement to Kurdistan’s efforts to autonomy in “Canadian Lessons for Iraq” (2005). Like Kurdistan, Canada is a nation of multiple distinct peoples, referred to as the “three pillars” of Aboriginal Canada, French Canada, and English-speaking Canada. While Canada has gone through a wholly different process of nation and state-building from Iraq, some of the mechanisms that it has established for power-sharing, resource-sharing, and social solidarity are useful in finding ways forward in making Iraq a functioning federal state.

Power-Sharing

Federalism is usually defined as the deliberate coming together of equals to establish a mutually useful governmental framework within which all can function on an equal basis. An essential tenet of federalism is the formation of power-sharing mechanisms between different levels of government. What makes Iraq unique is that, while it is legally a federal state, the status of a federal “region” only applies to the Kurdistan Region. The constitution provides a pathway for other governorates to form regions, but, like many other parts of the constitution, this has not yet been realized. The rest of Iraq functions as a unitary state with highly centralized power, which raises doubts about power-sharing at the federal level.

There is no consensus on what federal power-sharing should look like in Iraq. The constitution outlines multiple powers to be shared between the regions and the central state, but it does not provide a mechanism for negotiating these powers. Furthermore, previous attempts to implement power-sharing have been unsuccessful. The federal government has not enacted the Provincial Powers Law as intended. Instead, the Kurdistan Region operates with a degree of autonomy. However, conflicts persist regarding shared powers, including control over finances, territory, security, and natural resources.

Power-sharing in Iraq is increasingly fraught due to the absence of legal consultation mechanisms between the Iraqi government, its federal regions, and the decentralized governorates. Although the constitution mandates the establishment of a Federation Council composed of representatives from regions and governorates, no such council has been formed.

Additionally, the court system plays a crucial role in power-sharing by resolving disputes and establishing workable precedents. However, the Iraqi Federal Court is deeply dysfunctional. The envisioned court outlined in the constitution was never established, and instead, a transitional court has been functioning in its place. The court also frequently makes decisions on highly politicized cases, raising concerns about its independence and impartiality as an arbitrator.

The lack of a proper legal consultation mechanism for establishing power-sharing severely undermines federalism in Iraq.

A better approach can be observed in the Canadian model. In Canada, all territories are federalized as provinces, although the degree of autonomy varies. While there are defined powers for both the provincial and federal governments, many powers are shared in a complementary manner. Using the principle of asymmetry, provinces have the ability to allocate federal resources as they deem fit and can opt out of programs when they wish to exercise their own autonomy. An example of this is Quebec’s establishment of its own pension program.

This Canadian model may prove to be a suitable framework for Iraq, where there is a need for a clearer separation of powers. Not all regions desire to be governed with the same level of autonomy as the Kurdistan Region, or they might desire it, but political parties may prevent its realization.

Resource Sharing

Another essential aspect of federalism in Iraq is resource-sharing. Iraq possesses the world’s fifth-largest oil reserves, constituting over 99 percent of its exports. The Kurdistan Autonomous Region alone holds approximately one-third of Iraq’s total oil reserves, making resource-sharing a highly sensitive issue. However, the constitutional framework for federal resource sharing remains vague. Article 111 states that oil and gas are owned by all the people of Iraq in all regions and governorates, which lacks specificity. Article 112 stipulates that the federal government should manage and distribute revenues from oil and gas fields, but only those that were operational in 2005. Given that the lifespan of oil and gas fields typically ranges from 15 to 30 years, this means that there is no constitutional framework for many of the natural resources in present-day Iraq.

Without a concrete framework for resource sharing, the Kurdistan Regional Government and the Iraqi federal government have resorted to several unofficial agreements. However, these agreements have often led to unnecessary conflict that could have been avoided with a clear constitutional principle for resource sharing. According to E. Belsar, the federal government generally allocates a defined share of the oil income to the Kurdish region. Although this transfer should amount to 17%, it has varied between 13% or less and up to 23% depending on factors such as oil production, prices, political climates, and power dynamics. This uncertainty creates dysfunction.

For instance, when Baghdad reduced Kurdistan’s federal budget in 2014, the Kurdistan Region began independently exporting oil. However, both the Federal Supreme Court of Iraq in 2022 and an international court in 2023 invalidated this move, resulting in a halt in oil exports that economically harmed people across both Iraq and the Kurdistan Region.

In contrast, Canada has a constitutional framework governing resource-sharing, resulting in less volatility. Provinces have jurisdiction over natural resources, local taxation, and local public works, as further clarified by a 1982 amendment. This constitutional clarity minimizes conflict and inefficiency. Additionally, Canada employs the principle of equalization, where the Government of Canada addresses fiscal disparities between provinces from general revenues. In Iraq, establishing a constitutional norm similar to this would address the constantly fluctuating transfers of oil income and strengthen the federal state.

Ethno-Sectarian Politics in Iraqi Federalism

In Iraq, ethno-sectarian politics persistently dominate, and the poorly conceived federal system exacerbates disputes over land, resources, and power. Given the recent history of civil war, constructing a cohesive federal Iraq poses significant challenges. Building a stronger political system necessitates fostering social solidarity within the realm of politics.

In contrast, Canada has already undergone this process. As famously stated by Phillipe Couillard, Premier of Québec, “I am a Quebecer, and proud of it. I am a Quebecer, and this is my way of being Canadian.” The federal system in Canada allows for the formation of unity and solidarity. The French Canadian and Aboriginal populations hold significant status within the Canadian national identity, with protections for their languages and cultures. Iraq has a long way to go in developing the power and resource-sharing systems that Canada possesses, but it is crucial to look outwardly and evaluate how Iraq can enhance its federal system.

In Iraq, ethno-sectarian politics continue to dominate, and the poorly conceived federal system gives fuel to disputes over land, resources, and power. With a recent history of civil war, it will be difficult to build a coherent federal Iraq. There is a need for social solidarity in politics to build a better political system.

——————-

This article was originally published by Washington Kurdish Institute

Infowelat Enformasyon Ji Bo Welat

Infowelat Enformasyon Ji Bo Welat