We don’t want to impose our solutions by force, we want to create a democratic space. We don’t see armed struggle in the classic sense of previous guerrilla wars, that is as the only way and the only all-powerful truth around which everything is organized. In a war, the decisive thing is not the military confrontation but the politics at stake in the confrontation. We didn’t go to war to kill or be killed. We went to war in order to be heard.

Subcomandante Marcos

On the morning of January 1, 1994, around 3.000 armed Zapatista insurgents seized towns and cities in Chiapas, inhabited to roughly one third by indigenous peoples, claiming cultural autonomy, land rights, democratic participation and resistance against the neo-liberal strategies of the Mexican government. Armed clashes ended on January 12, 1994, the EZLN retired to the jungle and the armed resistance left space to a broad, still growing political movement. Ever since the State and Federal Government and the Zapatistas pursued a policy of negotiation, while the EZLN developed a mobilization and media campaign with the worldwide famous declarations of the Subcomandante Marcos. This strong media presence prompted numerous international left-wing groups to support the Zapatista movement, a shining signal for militant commitment and popular movement for indigenous and social rights not only in Mexico, but in many other parts of Latin America. The Mexican government tried to repress the movement with all means, including military aggression. The EZLN, which since 1994 has not carried out any new military operations, considered this step as a logical consequence of the treaty with Mexico of San Andrés of 1996 referring to cultural autonomy and indigenous rights.

The “Caracoles of good government”

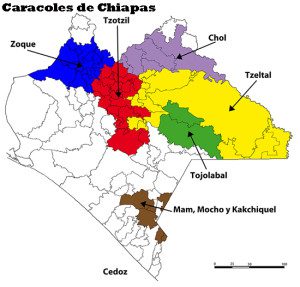

In August 2003, five larger areas under control of the Zapatistas in Mexico’s federated State of Chiapas, inhabited by some 300,000 people, gathered to form an unofficial ‘autonomous Zapatista region’, composed by 32 single municipalities. These local autonomies were also called “Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities (MAREZ), where assemblies of local representatives form the Juntas de Buen Gobierno (Council of good government). The municipalities, mostly very poor and economically backward, declared autonomy and established structures of democratic self-governance. These are not recognized by the federal or State Government, but allowed to oversee the local community programs on food, health, education and taxation. They provide for basic services in justice, health, education, land management, labour market, nutrition, commerce, information, culture and local transport.

The MAREZ, in Chiapas also called ‘caracoles’ (shells), tried to set up an autonomous health assistance, school system, trade network and productive activities in cooperatives. But the core of the autonomy claim remains the cultural distinctiveness, inspired by indigenous languages, community life, religious beliefs and values. According to EZLN statements, the Zapatista movement is not questioning the sovereignty of Mexico in Chiapas. Autonomy by the EZLN is seen as a device to achieve two major aims for the indigenous peoples: equality as Mexican citizens, which means an end of social and economic discrimination of the indigenous and poor small farmers; second the right to diversity, which means full recognition of the ethnic–cultural peculiarity of the indigenous peoples. The ‘Autonomous Zapatista Region in Chiapas’, despite being de facto autonomous, is no ‘territorial autonomy’ in strict sense, as it is not recognized by the Mexican state as a de jure arrangement and thus does not form a part of the multi-level government system of the Federal State of Mexico. The Chiapas government has even not recognized the local autonomy of the Indigenous peoples in its “Law on Indigenous Culture and Rights” of April 2001. Thus it does not correspond to the criteria of an official regional autonomy as outlined in my work on “The World’s Modern Autonomy System” (on the Internet).

In ist first 10 years the “Caracoles de Chiapas” have achieved documented improvements in the areas of gender equality and public health, but they did not succeed in establishing a genuine territorial autonomy of the Caracoles. The EZLN, being a political-military apparatus, declared that the self declared autonomous area MAREZ (Councils of Good Government) marked a transition where the EZLN military would no longer give orders in civil matters in the autonomous communities. On August 8, 2013, the Zapatista invited the world to celebrate 10 years of Zapatista autonomy in the 5 Caracoles di Chiapas, but the basic issue keeps unresolved, whether this unilateral form of autonomy should transform in an officially recognized form of territorial autonomy within the State of Chiapas.

Thomas Benedikter

Infowelat Enformasyon Ji Bo Welat

Infowelat Enformasyon Ji Bo Welat