C.K. Garabed (a.k.a. Charles Garabed Kasbarian) has been active in Diasporan Armenian community organizations all his life. As a writer and editor, he has been a keen observer of, and outspoken commentator on, political and social matters affecting Armenians.

For more than 40 years, his writings have appeared in the Armenian press in the Diaspora. The year 2014 marks the 25th anniversary that Garabed has been a regular contributor to “The Armenian

Weekly.” There, he produces a weekly column called “Uncle Garabed’s Notebook,” in which hepresents an assortment of tales, anecdotes, proverbs, poems, riddles, and trivia. For the past 10 years, each column has contained a deconstruction of an Armenian surname whose language origins may be Armenian, Persian, Kurdish, Turkish, or Arabic.

Earlier this year, his “Dikranagerd Vernacular Handbook” was published. A sort of dictionary, it contains hundreds of words and expressions from the Armenian dialect of today’s Diyarbakir.

In the following interview with Necat Ayaz, Garabed discusses his ancestral history in and culture of the Diyarbakir region, the preservation of the Armenian identity in exile, and prospects for developing Kurdish-Armenian relations.

Necat Ayaz: You first came to our attention with the online publication of your Dikranagerdtsi Vernacular Handbook. Before we discuss the Handbook, we’d like to ask you about your background. Your parents were originally from Diyarbakir, which you call Dikranagerd. What can you tell us about your family history?

Kasbarian: My father’s mother, Mariam, was an Alipounarian. The Alipounarian clan took its name from the village of Alipounar, which lies west of the city of Diarbekr, within walking distance. I understand the name of the village comes from Ali Pounar or Ali’s Spring. Dikran (Spear) Mgunt, in his book Echoes of Amida (Amidayi Artsakankner) published in America in 1950, states that in the 19th century, the village was comprised of 40-50 families of three races, Armenians, Chaldeans, and Turks, living in separate enclaves.

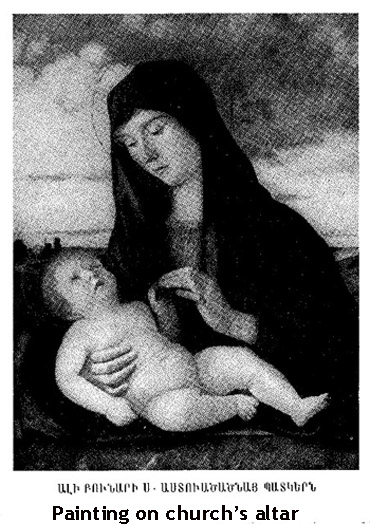

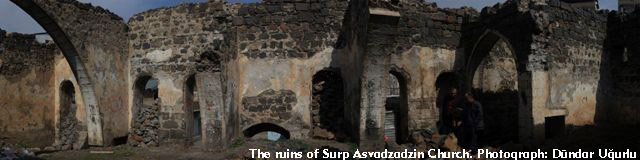

My father’s father, Der Kasbar, was the village priest of Alipounar, his church’s name being Sourp Asdvadzadzin, Holy Mother of God. My father told me that it was a big church with rooms to accommodate pilgrims who stayed overnight. In his book, Mgunt states that swallows had built a nest in the church, and would sing along whenever the Divine Liturgy was performed.

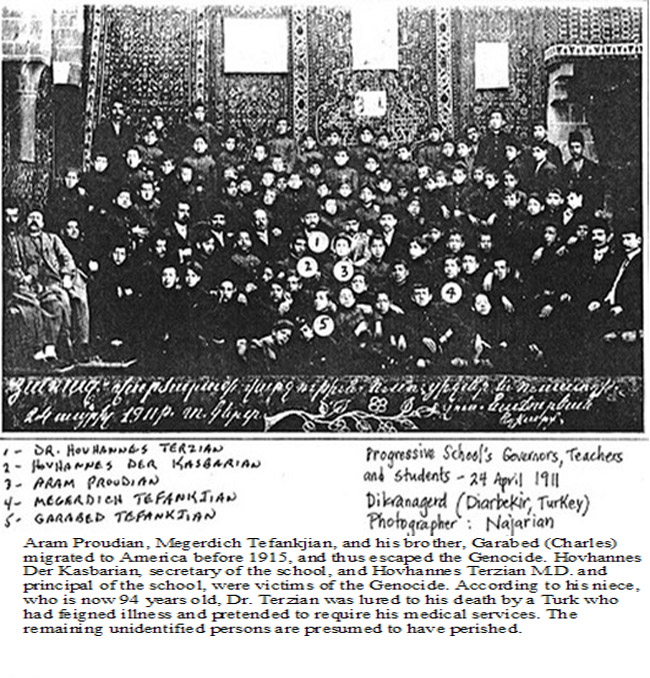

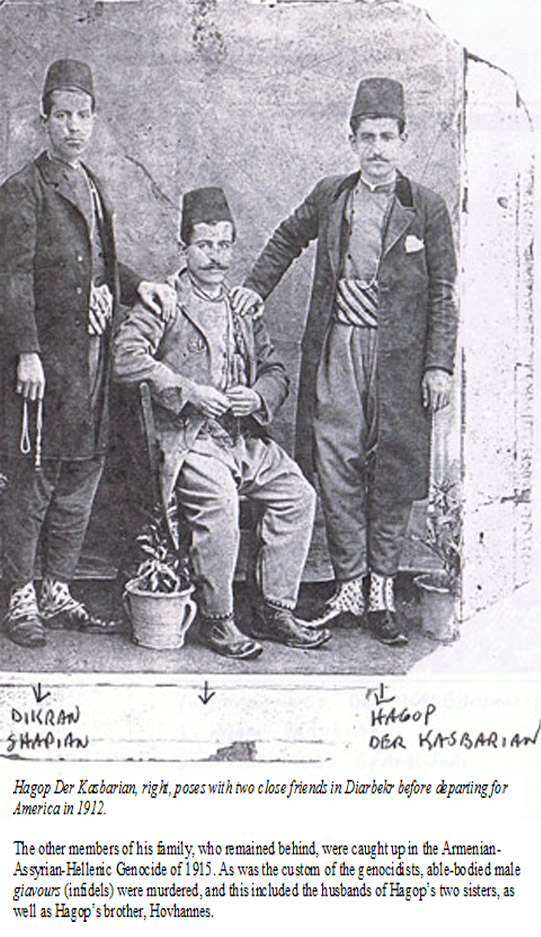

Der Kasbar was killed, along with his eldest son, Garabed, whose name I bear, in the Hamidian massacres of 1895. He left five other children, which included my father, Hagop, who later migrated to America.

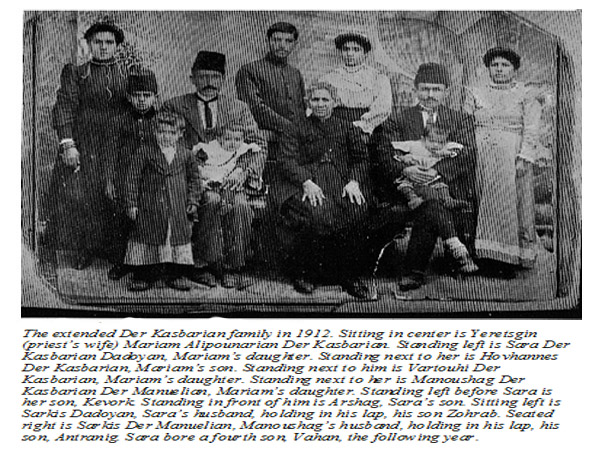

The other members of his family, who remained behind, were caught up in the Armenian-Assyrian-Hellenic Genocide of 1915. As was the custom of the genocidists, able-bodied male giavours (infidels) were murdered, and this included the husbands of Hagop’s two sisters, as well as Hagop’s brother, Hovhannes.

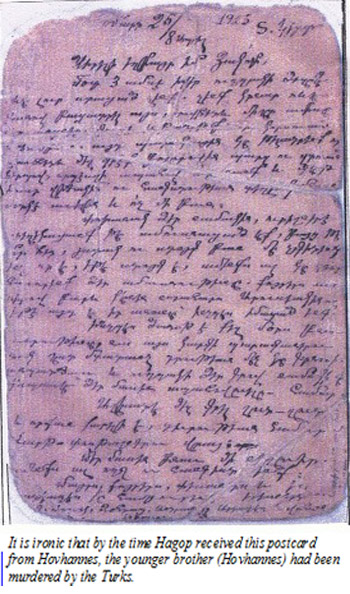

See photograph of postcard below, with English translation, sent by Hovhannes Der Kasbarian to his older brother, Hagop,in America.

“March 25/8 April 1915 D.Gerd (Dikranagerd)

My dear brother Hagop,

We have not received any direct news from you for close to three months. We cannot explain this because your letters always arrived within a month. We can guess that they got lost on the way. In that case we suggest that from now on you write to us in a very concise, simple way so we can receive it securely and thus learn of your situation and well-being. Nothing more than that.

Instead of a letter from you, we heard from others that you have gotten married. But to whom? We do not know anything clearly and for sure. Anyway, if it is true, we all congratulate your wedding. My sisters also send their love and greeting to the new bride, Arousiag, if that is her name as we had heard. As our mother’s character is known to you, she is in a state of anxiety when in similar situations. She absolutely awaits to receive a letter directly from you with your handwriting to hear that you are safe and sound. Try to write to us more often and as much as you can on post cards to make it easy. Do not worry about us. We are all well and alive.

Our mother, sisters, brothers-in-law and I warmly embrace you and kiss your cheeks. Greetings also from your nephews Kevork, Arshag, Zohrab, Antranig, Ardashes and Vahan.

Hovhannes.”

My mother, Lousia, was from the city, and was exiled in 1915 along with her mother, Touma, and two infant children. Lousia’s father and her husband were victims of the Genocide, and her two children perished in the murderous march through the Syrian Desert. Ironically, my mother succeeded in preserving the deeds to properties in Dikranagerd that belonged to her husband and his family who were all liquidated in the Genocide. She also made a point of preserving as much of the culture she was forced to abandon, including the traditions, cuisine and dialect of Dikranagerd.

Necat Ayaz: What an amazing coincidence! Our editor’s family roots also go back to “Elipar,” as we say it. In fact, his two uncles still reside there. Our editor visited the area last week with photographers who took pictures of the village, and the church you mention, which is shown elsewhere in this interview.

How have Armenians been able to continue their identity and culture despite living in their Diaspora for the past one hundred years? Considering the pressures of the “American way of life” which is based on individual values rather than the collective ones, and the level of integration of Armenian-Americans into English speaking mainstream society, what do you think about the chances that Armenian-Americans can continue their group identity?

Kasbarian: Any time a people are separated from their indigenous lands, we will also regrettably see a departure from the native culture. It is difficult to authentically replicate that culture without environmental reinforcement, and it requires formidable effort to resist the influences of a new dominant culture that might not always be preferable or superior to the old one.

My parents succeeded in passing on to their children the language and customs of the Armenians at the cost of a great sacrifice of their ability to succeed materially in the New World. By making Armenian the language of the home, they saddled themselves with broken English for the remainder of their lives, and we were the beneficiaries of that sacrifice. The same can be said of my wife’s family.

To get an idea of our children’s involvement in Armenian matters, visit the web sites with which they are affiliated:

http://www.tufenkianfoundation.org/ and http://www.lucinekasbarian.com

To a degree, I fault our clergy for not discharging their responsibilities as leaders of the Armenian community, which has led to the precarious condition of our culture in exile. Whenever officiating at weddings of our young couples, had they given them advice, when blessed with children, to make Armenian the language of the home, and have their advice taken, we would be in much better shape today as Armenians.

For those of your readers who are interested in a comprehensive treatment of the subject, there is a lecture I delivered some years ago about the future of Armenian culture in America, the transcript of which is available here:

http://www.armeniapedia.org/wiki/Armenian_Culture_in_America:_Dead_or_Alive%3F

Although it has a pessimistic tone to it, I am including it here in the hope that the “hidden Armenians” among you will come forward to declare their Armenian identity, and perhaps form a nucleus around which Armenians in the Diaspora can rally.

Necat Ayaz: Regarding your Dialect Handbook, when and how did you begin to compile words, expressions, phrases and other useful information? What are the difficulties of preparing a dictionary in your Diaspora?

Kasbarian: Sometime about 1970, I began recording whatever I knew from speaking to my parents and members of the Armenian community at large. After all, the Dikranagerdtsi dialect is my native language. I made entries in a notebook in my spare time. It started out mainly for self-amusement. As the years went by, I realized that a written record of our dialect was an important undertaking, and therefore took my task more seriously. With the advent of personal computers, I transcribed whatever I had recorded, until it grew to a size that was feasible to pass on to the public. “Dikranagerdi Parparuh,” a textbook on the Dikranagerdtsi dialect, had been published in Armenia back in 1978 and which I’m sure was useful to many persons who were interested in becoming knowledgeable of the dialect. However, I found it lacking in that it’s vocabulary did not include many Turkish, Kurdish, and Arabic words. Without those borrowings it was not a realistic portrayal of the way our forebears spoke on a daily basis.

Producing this Handbook was not a difficult undertaking for me personally because I merely recorded what I knew. Whenever I was not sure of the meaning of a term, or even its pronunciation, I would seek help from my friends and relatives. As far as the difficulty of publishing a book that is so specialized, and of limited interest among non-Armenians, I avoided that difficulty by choosing to publish only online in order to make it accessible beyond our borders, and at no charge.

Necat Ayaz: Is the dialect still spoken by Armenian-Americans who are originally from the Dikranagerd region, that is now called Amed (Diyarbakir) by Kurds?

Kasbarian: Yes, there are some Armenian-Americans of my generation that converse in the dialect whenever they get together, which is less frequent as time passes. Not many of the younger generation make use of it, although they may fully understand. It has become a vehicle for humorous banter more than anything else.

You’ll notice that I spell Diyarbakir as Diarbekr. There’s a reason for that. My understanding is that the ancient name of the city, Amid, is of Assyrian origin, and that when the Romans colonized the city they called it Amida. Following the Romans, the Persians came to power and were succeeded by the Muslim Arabs. It was the leader of the Arab Bekr tribe, who renamed the city Diar Bekr, meaning – the country of Bekr. Much later Mustafa Kemal gave the city its current name Diyarbakir, which was derived from the copper ore that exists there. Diarbekr is the spelling that appears on many old maps, and is used by writers on the subject, such as Gertrude Bell, as well as H.F.B. Lynch*, who surveyed all of Armenia, east and west, and drew a map that showed all the cities, towns and villages with their old names, before they were changed. You can see the villages surrounding Dikranagerd where my relatives lived, such as Alipounar, Hazro, and Haini.

Necat Ayaz: What are the exact borders of the historical Dikranagerd region? Considering the vast geography where Armenians lived, what are the other dialects Armenians have spoken? Did any dialect become extinct after the Armenian scattered around the world?

Kasbarian: I don’t know if I can answer the first part of your question; however, your readers can inform themselves of the history of Dikranagerd, and Diarbekr, whose ancient name is Amida, as we say it, by viewing a video that contains a slide lecture by Dr. Herand Markarian. It can be accessed at the following URL, documenting a cultural evening celebrating the Dikranagerd Armenian heritage: (Advance to the 31 minute mark of the video)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5-JZzfXzSIE&feature=youtu.be

As far as dialects go, every city with its surrounding villages had its individual way of speaking. Kharpert (Elazig), Sepastia (Sivas), Moush, Palou, Yerzinga (Erzincan), Erzerum, etc. all differed to some degree. Some did not depart radically from the standard Armenian language; some did. Dikranagerdtsi is difficult for other Armenians to understand because of the heavy borrowings from neighboring languages. Dikranagerdtsis have two ways of pronouncing the letter (a). There is the standard pronunciation as in the English word bar. Then there is the flat (a) that is borrowed from Arabic, Persian and Kurdish, such as in the English word hat.

I’m not able to say which dialects have become extinct, if any. I’m sure some are on the border of extinction.

Necat Ayaz: Was there a standard Armenian language spoken in the region you call Western Armenia and used by Armenian political, educational and other organizations?

Kasbarian: Definitely. Those Armenians who are partial to the Eastern version of the Armenian language sometimes refer to Western Armenian as a dialect of the original language. This would be like saying that French, Italian and Spanish are dialects of Latin. However, they are viable and distinct languages, and so is Western Armenian. A vast body of literature has been composed in Western Armenian, which is the version used by most Armenians outside of the Republic of Armenia and Iran. The texts of many folk songs from the villages of Western Armenia include many terms intrinsic to Western Armenian and reflect the influence of Turkish and Kurdish.

Necat Ayaz: Do you have any information regarding the language influences of Armenian on Kurdish and Kurdish on Armenian? Can you give some examples?

Kasbarian: I don’t know about the influence of Armenian on Kurdish, but I can give you an idea of the influence of Kurdish on the Dikranagerdtsi Armenian dialect. There are scores of words from Kurdish that we still use, For example:

Adǎt: custom

Akhur: end, outcome

Alav: flame

Azab: bachelor

Bǎg: feudal lord, ace in card-playing

Betǎr: worse

Chamour: mud

Dǎrǎjǎ: staircase

Dǎvǎ: camel

Furchǎ: brush

Hǎrs: anger

Jǎgh: fence

Kǎchǎl: bald

Mala mineh: All my home and family have disappeared. (Used to describe a child’s idea of disaster.)

Peshgir: towel

Shor: salty

Shorba: soup

Tǎshkǎlǎ: tumult

Toutkal: glue

Zad: meal, stew

The well known and beloved Armenian folk song Dle Yaman is a case where Armenian has been influenced by Kurdish. Dil means heart in Kurdish, and dle means my heart. Yaman, in my opinion, is a mispronunciation of aman, which means grief or sorrow. Thus, dle aman can mean my grieving heart, or my sorrowful heart, which matches the lamenting nature of the song.

Necat Ayaz: The Turkish rulers created barriers between Armenians and Kurds who were native inhabitants of the same country and they succeeded with this project by using Kurdish people in the Armenian Genocide. We know the rest of the story of Armenian-Kurdish relations, which has continued to be marked by a lack of contact. As an Armenian intellectual, what do you suggest to start mutual relations in this regard and what kind of responsibilities could both players have? The remains of Sourp Asdvadzadzin Church in Alipounar photographed under the guidance of our editor could perhaps be a starting point. Do you think Diasporan Armenians would like to see it restored? If so, would they be willing to contribute to the funding of the cost of renovation?

Kasbarian: First of all, when you refer to me as an intellectual, I must inform you that I do not approve the use of that word as a noun. It is pretentious sounding. As an adjective it is perfectly fine. One can have intellectual pursuits or curiosity. Now, to try to answer your question, I am not a member of any political party, nor do I occupy a position of authority within Armenian community organizations. I merely offer my views as a writer on matters that affect the Armenian community at large. The best I can do is to appeal to my fellow Armenians to make their views known to our leaders, and hope that these leaders possess the wisdom to pursue a policy that has popular support. But first, our rank and file Armenians must be alert as to what our future is likely to be without a recovered homeland.

From informal polls, today, we know that now, more than in decades past, Armenians are traveling to Eastern Turkey to visit their ancestral lands. The successful undertaking by the global Armenian community to renovate Sourp Giragos Church in Dikranagerd is a good indication of the strong ties that many Armenians still feel for their homeland. We also know that many Armenians claim they would develop ties with their ancestral lands if they felt they could safely do so. This could include but not be limited to Armenian refugees from the war in Syria, whose ancestral homeland is in modern Turkey. But other Armenians claim they would not return, even to visit, because they do not wish to feed a Turkish economy that has already inherited and benefited from the theft of Armenian wealth and property. Perhaps generating and publicizing a census regarding individual intentions of Armenians with regard to their ancestral lands will clarify the issue. Such a census should include a reference to Sourp Asdvadzadzin Church in Alipounar to determine if the Armenians living abroad would be interested in helping to restore the church.

As far as historical Kurdish-Armenian relations are concerned, we Armenians, from our perspective, are aware of the injustices we have suffered at the hands of the Kurdish Begs, as exemplified in the well-known novel, Khentuh (The Fool), written by Raffi (Hagop Melik Hagopian) in 1881. It is available in Armenian and English translation, but has yet to be translated into Kurdish and Turkish. One English translation of The Fool by Jane Wingate in 1950 is now in the public domain and freely available online here: http://www.cilicia.com/armoz.html

And now, if I may, I invite your Kurdish colleagues to ask themselves the following questions on Kurdish-Armenian relations.

Have any of your Kurdish colleagues touched on this subject? What is the thinking among rank and file Kurds, especially in the Dikranagerd region? It’s all well and good for Abdullah Demirbaş, mayor of Sur in the province of Diyarbakir, to invite Armenians back. But does that reflect the thinking of those Kurds who are currently occupying property of the ancestors of those very same Armenians? Would your Kurdish colleagues like to see the forming of dialogues and alliances with Armenians of the Diaspora? If so, to what extent?

——————-

- Note: Lynch’s two volume work “Armenia: Travels and Studies” was published in London in 1901, and remains the definitive account in English of Armenia before the 1915 massacres. An Armenian translation of the book was published in London in 1902, and another in Constantinople in 1913. In modern Turkey, until at least the late 1990s, the book was on the official list of banned books.

# # #

——————-

- Note: This interview was first published in Infowelat in 2014.

Infowelat Enformasyon Ji Bo Welat

Infowelat Enformasyon Ji Bo Welat